This week, I lost a four-way debate on BBC Radio 4’s Best Medicine. The best medicine is, I gently suggested, gardening. Apparently not everyone agreed! You can listen to the episode here on BBC Sounds. And now I’ll have a bash at convincing you sensible people to come ‘round to my way of thinking.

Most obviously, the garden is a really healthy place to spend time – physically and mentally. The organisation Thrive recognise this – and if you’re interested in how gardening can make positive changes in someone’s life, you should follow the link and take a peep at what they do. And support them, if you can.

But there’s also a much deeper (and more obscure) reason that gardening is the best medicine: without gardening, there would be no skin grafting. Ergo, gardening has saved countless lives! Okay, it’s a bit of a stretch, but it’s still a golden opportunity to tell you how skin grafting has its roots(!) in horticulture. To do that, we need to go back nearly 500 years, to the 1540s.

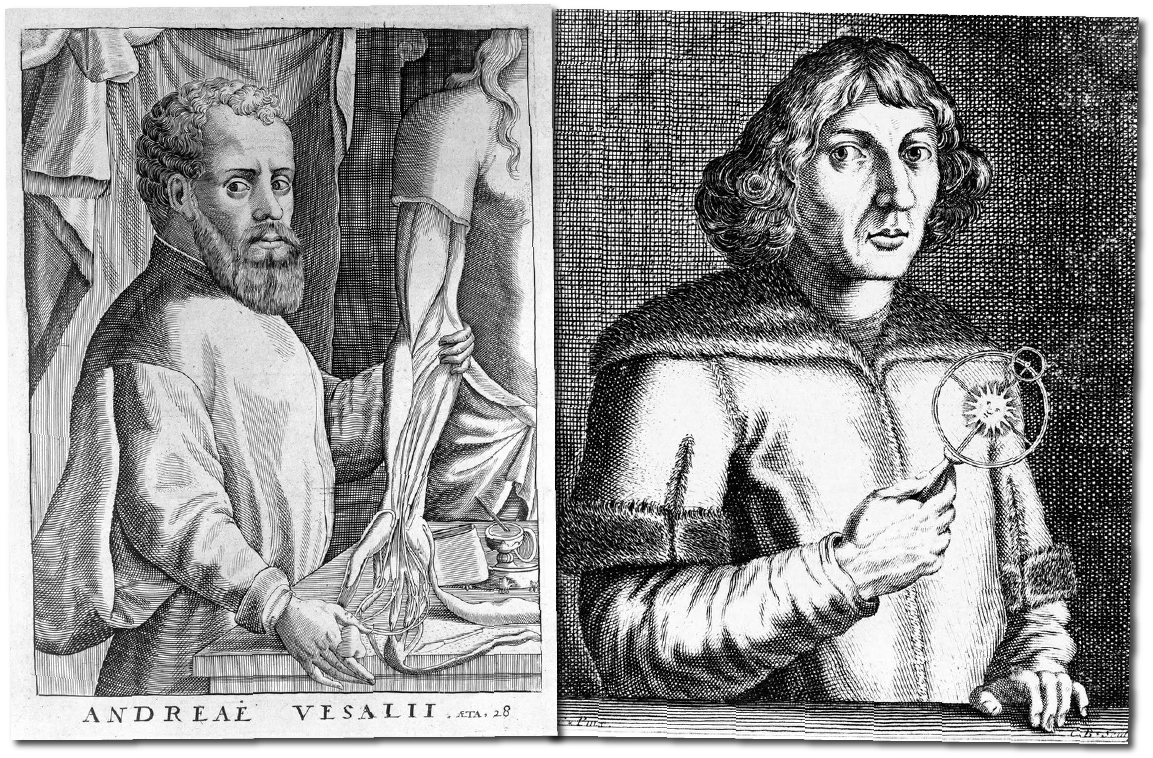

It’s the Renaissance, the great age of geographical and scientific exploration and discovery. In fact, the word ‘exploration’ came into the English language around this time – 1544 is the first recorded usage. The word ‘discovery’ came a bit earlier. If you know anything about the history of medicine, you’ll already know about Andreas Vesalius, who for the first time systematically dissected the body and described what he saw. His great work, De humani corporis fabrica (‘on the fabric of the human body’) was published this decade, and it started to undermine faith in traditional medical systems. In exactly the same year, Copernicus placed the sun at the centre of the solar system. The scientific world was vibrant back in the 1540s, with discoveries of new lands and even new, controversial kinds of knowledge.

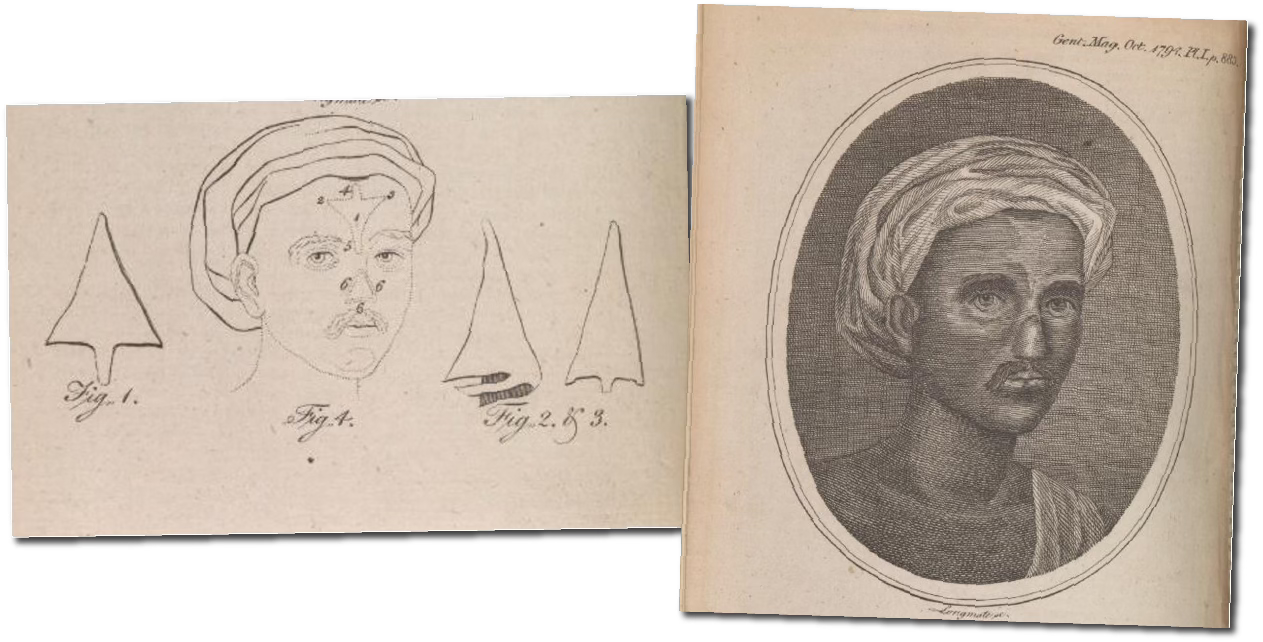

The first record of a modern transplant also comes from this decade, in 1549. But it was emphatically not part of the scientific revolution that seems to characterise the age. The only kind of transplant available at this time was a skin graft, but they’d been around, unchanged, for centuries and had been described as far back as the sixth century BC (see the image above). Since then, they’d disappeared from the records only to re-emerge in Renaissance Italy, as a secret technique performed exclusively by peasant surgeons in Italy. These surgeons would fashion new noses, lips and ears from the skin on a person’s forehead or forearm. So, at this time, skin grafts were closely guarded secrets. Only a handful of surgeons knew how to perform them. That is, until someone stole the secret.

Meet Leonardo Fioravanti. He had no faith in the classical medicine and felt that what doctors did barely resembled healing. He was right, too. Doctors trusted ancient books in those days, more than they trusted their own senses. Take anatomy. If what an anatomist saw in the body deviated in any way from what they read, they’d blame the body for being an aberration. And this would pretty much always be the case because the anatomical descriptions that classical doctors relied on would invariably be Latin translations of Arabic translations of Ancient Greek Gaelic texts. Plus, the observations that Galen himself relied on were from animals.

Fioravanti, on the other hand, was vocal about his mistrust of medical men, and accused them of sending medicine ‘straight to the bordello’. He actually had a degree from Bologna, but abandoned his books in favour of the remedies told to him by old soldiers and out-of-the-way countrywomen. Their remedies, he could see, worked. Before you run away with the idea that Fioravanti was some kind of beacon of effective medicine in a barbaric age, I should mention that many of his remedies involved urine. Lots of them involve vomiting, too. And he once claimed to have visited a hospital of incurables, and cured everyone there. The secret of skin grafting was one of his only truly useful discoveries, and that came from a little fishing village called Tropea, in Calabria.

It was in Tropea that he met the Vianeo family – a close-knit family of surgeons who had carefully guarded the secret of skin grafting for generations. Then Fioravanti rocked up, knocked on the door and looked the surgeon straight in the eye and asked ‘can I watch you perform a skin graft?’

Understandably, the Vianeo family wasn’t too keen on letting this strange man watch them operate. But he told them that someone in his family had been fighting in Lombardy, and he’d had his nose chopped clean off. He’d heard there was a way to fix it, but before he’d countenance sending a family member for what seemed like a fabulous claim, he wanted to see it worked for himself. Now, losing your nose in a war would have been relatively common back then, so it was a convincing lie (he could have said his relative had been duelling, had syphilis, or lost his nose as a punishment, but I suppose war was most honourable way you could lose a nose). In any event, they did let him watch.

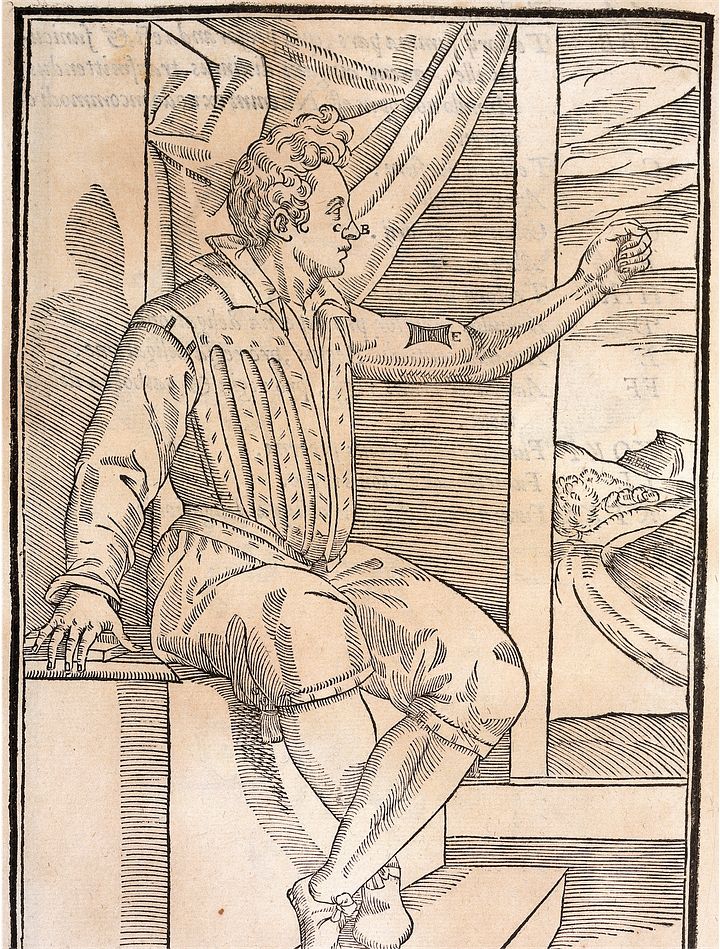

Leonardo Fioravanti shuffled into the operating theatre, and spent most of the operation with his hands over his eyes, making the appropriate noises of disgust. He didn’t like blood, he said, but he was really looking through the gaps in his splayed fingers and taking careful note of everything he saw.

A surgeon would probably insist on a slightly more complex explanation than what I’m going to give you, but what Fioravanti basically saw is the surgeons cutting a flap of skin out of their patient’s forehead (or maybe their forearm), and then making incisions around the place their nose would be. This would have created two open wounds they’d bind together, like you can see in the picture above (which is from much later, when the British ‘discovered’ the procedure in the nineteenth century). After a few weeks the surgeons could sever the connection between arm and face and the patient could happily go about with their new nose.

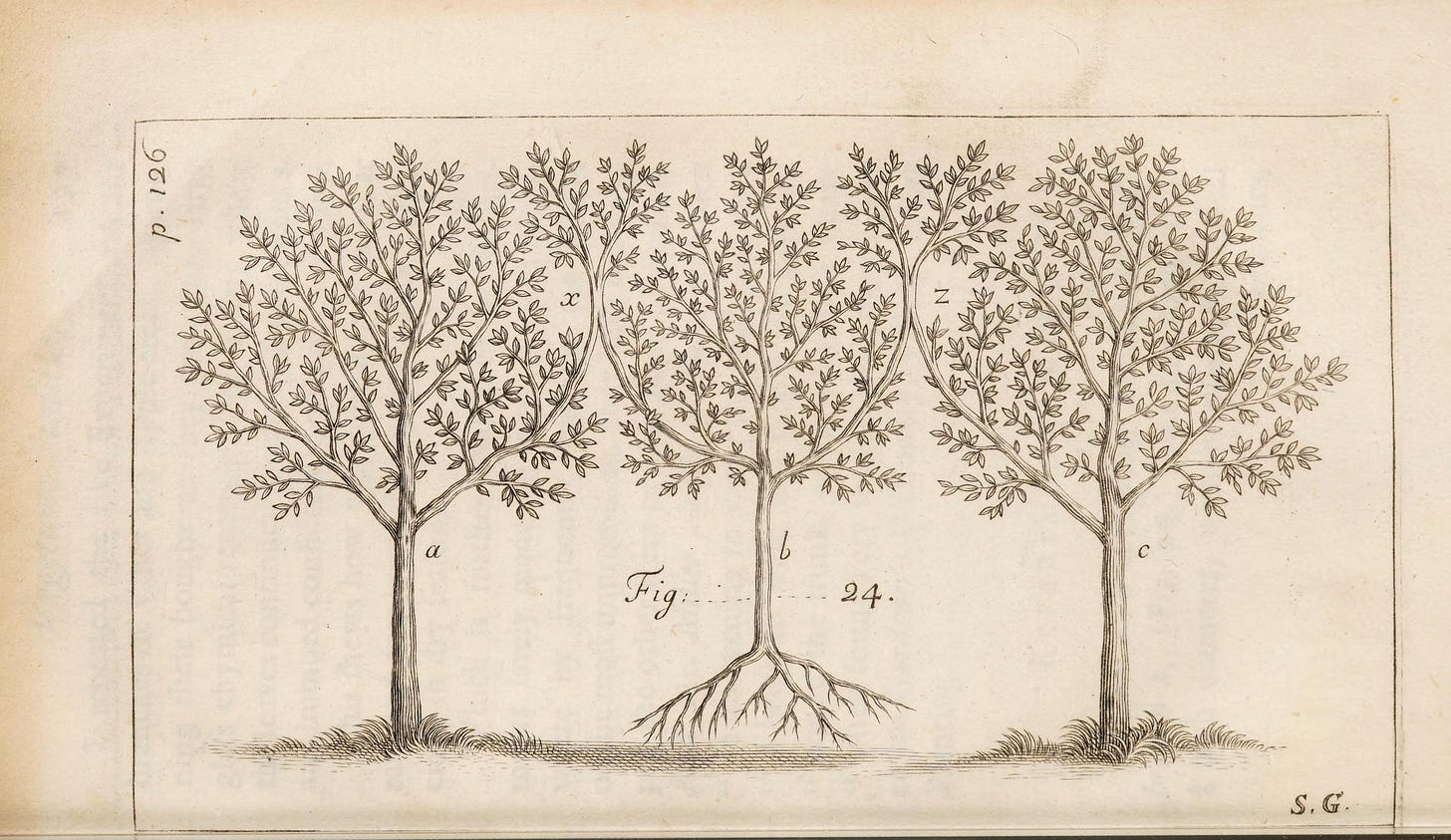

It turned out that this procedure is basically the same for plants. You just substitute skin for bark, and you have a horticultural graft (used to graft the branch of one tree onto the body of another). Like skin grafting itself, horticultural grafting is properly ancient and has always been widely practiced throughout the world. In fact, Leonardo Fioravanti knew that these surgeons were taking the horticultural operation and simply transposing it to humans. For him, the connection between the two operations was so strong he even described it as ‘the agriculture of the body’ and ‘the farming of men’.

Now, just before he died, Fioravanti introduced the secret of skin grafting to an academic at Bologna University called Cesare Aranzio, who was a bit of a chancer. Aranzio barely waited for Fioravanti’s corpse to grow cold before he stated putting it about that he’d invented the procedure himself. (He called himself ‘the first restorer of noses’.) It seems no one really believed him. But, thankfully, before he died, he taught the method to his student, a man called Gaspare Tagliacozzi. And it was in his book, De curatorum per insitionem libra duo (1597), that the skin graft was depicted for the first time.

And that’s how a horticultural operation performed on humans by Italian peasant families became a legitimate and properly studied surgical practice.

Before I leave you for the week, I also wanted to say that as soon as the skin graft became more widely known through Tagliacozzi’s book, that’s the moment when critics first started to accuse transplant surgeons of playing God. There were two ways you could look at skin grafting. One was that the surgeon was restoring the face, the other that you’re presuming to impose order on something that God has created. Most of his book, then, was about what classical thinkers and theologians thought about the perfect human face and nose. And then arguing that surgery was restoring that, rather than deforming it. By the time you got to his description, you’d hopefully agree. That’s why Taglicozzi’s book was enormous, despite the operation taking only a few pages to describe.

The last thing I want to say this week is this: I started this story by writing a bit about the Renaissance being a time for scientific and geographical discovery. It was also a time when people thought a lot about the difference between natural and artificial, and it wasn’t only surgery that troubled them. Gardening bothered them, too. Just like surgeons, gardeners threatened the divine order by deeming to shape the landscape that God had supposedly already ordered. And that’s why in Italian gardens from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries we get a lot of statues of monsters and depictions of Greek and Roman mythology. Because shaping nature, like shaping humans, supposedly created an abomination.

It’s funny to think how in the space of 50 years, skin grafts went from being the secret of farmers and peasants, who didn’t really care about these high-minded debates on nature and artifice, to being right at the centre of the same debates.

If you want to know more about transplant surgery, you can buy my book – it includes a story about Fioravanti pissing on noses (he liked urine and used it a lot).

And here’s a video I did a couple of years ago, about the origins of transplant surgery.

Robbed! You was robbed mate. Although having now read this and Spare Parts i feel you have argued convincingly the gift of the gab should be the Best Medicine. Without charisma and general gifted gabbery no surgeon would have ever convinced anyone to let them try out procedures on them and medical science would have plateaued at a wish and a prayer. “You want to what, sorry? Stitch my arm to my face and then piss on it?” Although correct me if I’m wrong but if I remember my history correctly I believe this is also the origin of the phrase “he doesn’t know his arse from his elbow”, as in the old saying: “before you let someone do a nose reconstruction check he knows your arse from your elbow”.