The Royal College of Surgeons and the Lancet – A Class War

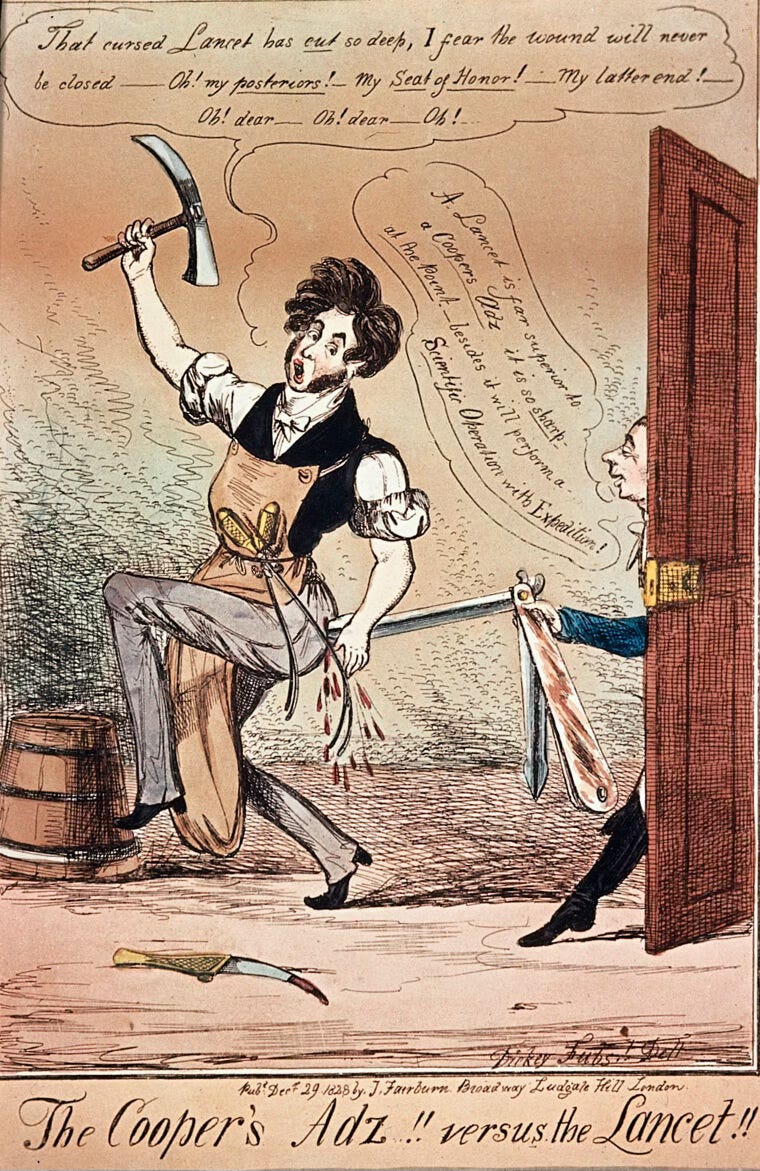

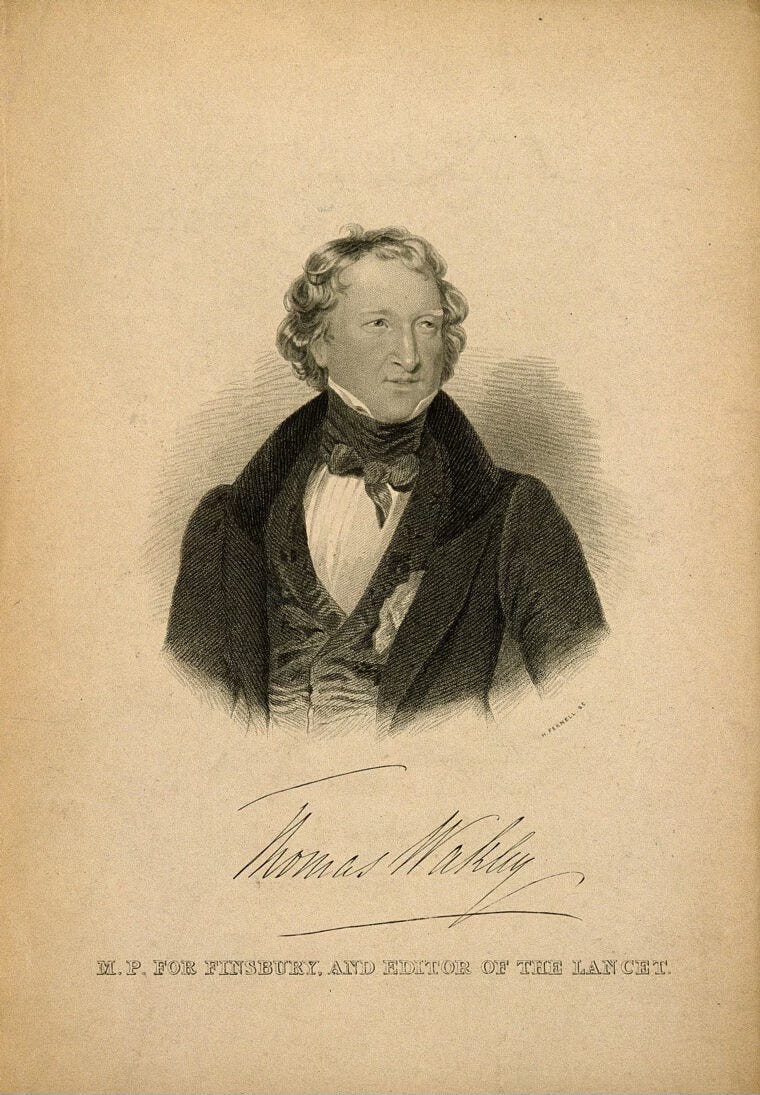

The Lancet is now one of the most famous, highly respected organs of the medical establishment. But its founder was a flowery waistcoat-wearing, loudmouthed, bullish sprig of fashion called Thomas Wakley, a surgeon-turned journalist who went after the corrupt and complacent. In February 1831, he attempted to dissolve the Royal College of Surgeons.

The Lancet and the Royal College of Surgeons had been scrapping for years by this point. It was, in a way, a class war.

The College leadership, more-or-less, were a cabal of wealthy surgeons. They held the top surgical jobs in the country, and kept them for life. Should one of their number expire, he’d be replaced by his or his colleague’s son, nephew, or high-paying apprentice. Although they had serious responsibilities, those heading the College were unregulated and tended to champion their own interests.

The Lancet, on the other hand, had since 1823 been standing up for the little medical man. We tend to think of doctors in history as well off. But that isn’t true. Thanks to various early ninteenth-century reforms I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, doctors had a lot of competition and a general practitioner might have earned as little as £50 per year (which was less than a skilled tradesman).

Wakley and the Lancet spent much of the 1820s needling, goading, and humiliating individual corrupt surgeons and hospital administrations.

By the 1830s, Thomas Wakley craved bigger victories. He’d clashed with the Royal College of Surgeons in the past, demanding an end to all kinds of corruption. But he’d only ever won tiny victories (now, thanks to Wakley, members could use the front door). His confidence was unbounded, though, and this made him plan and attempt ridiculous things. If the Royal College of Surgeons weren’t going to play nicely, he thought, he’d dissolve them entirely.

His chosen battleground was a lecture on hernias.

A Lecture on Hernias That Went Terribly Wrong

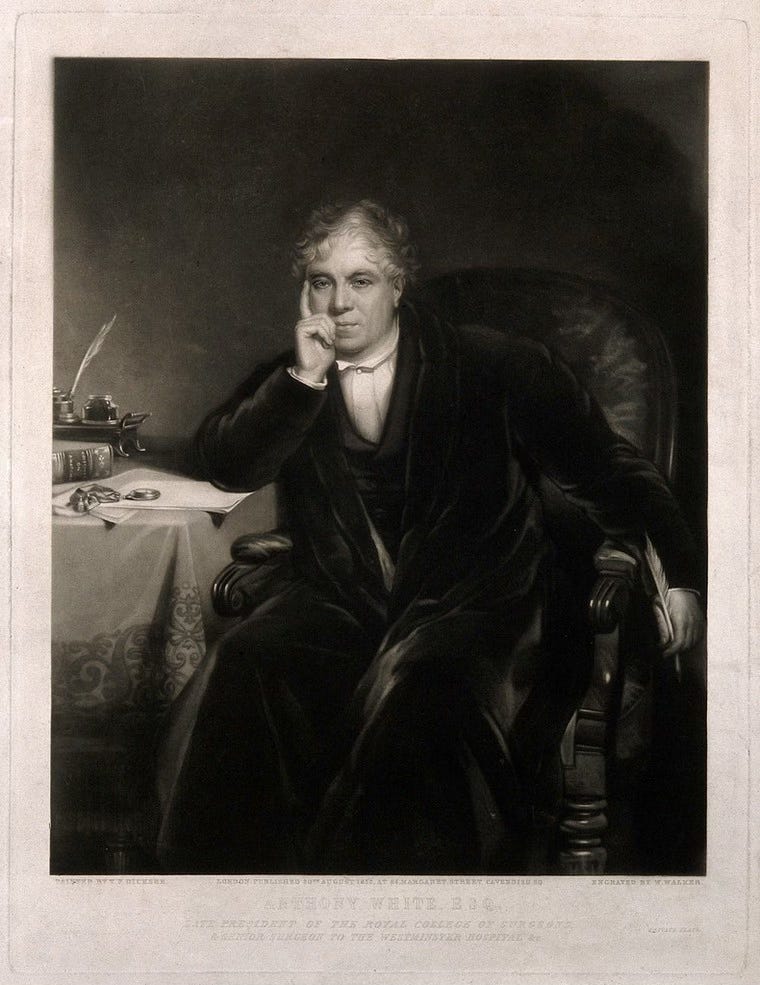

On 12th February, 1831, Anthony White – described by the Royal College’s of Surgeon’s own Lives of the Fellows as ‘the laziest man in his profession’ – was due to give a prestigious Hunterian Oration. He was delighted with the turn out. Hundreds of people. All here to learn more about hernias. Or so he thought.

His misconception was soon cleared up when Thomas Wakley made his entrance1, brushing the rain from his coat. The audience erupted into applause. They’d actually gathered on the pretext of defending naval surgeons, who had been excluded from official royal gatherings (actually, they hadn’t – it was a misconception caused by a printing error, but they didn’t know that at the time).

Wakley began to make a speech, which transformed the lecture audience into a meeting of disgruntled surgeons.

Poor Anthony White sat silently grasping his paper with both hands and staring straight ahead. With effort, the meeting was brought to order and the speaker allowed to stumble through his talk, trying his best to ignore the impatient shuffling. After his concluding words, there was a light smattering of applause and the Members continued their meeting as if nothing had interrupted it.

The Council of the Royal College of Surgeons – a body representing the pampered surgical elite – decided they’d better hear their members’ grievances about navel surgeons. And although some actually took Wakley’s side, most of the insisted that nothing could be done about the ship surgeons – if they were to be excluded from royal gatherings, then so be it.

But the naval surgeons weren’t really the issue.

A week later, Wakley made his way into the same lecture theatre. This time he found a crowd of 300-400 outside, locked out in February’s blustery weather. The doorman had been ordered to let no one through, ‘especially the editor of the Lancet’, until just before the lecture.

By the time the members burst in, they were wet, cold and irritable. Their calls for Wakley to speak amounted to ‘nearly a riot’. The Council arrived, all gowns and frowns, this time joined by several Bow Street Officers.

Wild disorder surrounded a calm, composed and silent Wakley, staring down his opponents. A councillor sent one of the officers to order him out. But those surrounding Wakley blocked him. The Council, Wakley blandly stated, doesn’t have the power to remove him. The officer returned to the Council. ‘Mr Wakley knows perfectly well what he’s about’, he said. The Council filed out of the theatre, leaving it full of disgruntled surgeons.

Wakley refused the same order to leave when it was delivered in writing. A group of Bow Street officers then approached and picked Wakley up by the collar, arms, and legs, hoping to expel him by force. The Members came to Wakley’s aid, fighting over his body. No sooner had Wakley regained his upright position than one of the officers aimed a truncheon at his head, missed, and hit his shoulder.

Wakley’s early years boxing came back to him in a flash, and the fighting started in earnest, a riot in the lecture theatre. Soon seeing respectable men thrown over benches around him, though, Wakley finally consented to leave the building, urging his friends to come along without resistance. Two officers, hands on his shoulders, escorted him out of the building.

Once the officers released their grip, Wakley called over two other officers who happened to be patrolling the streets. He explained what had happened and showed them where the truncheon had hit. So, the passing officers arrested the one who landed the blow on Wakley, and Wakley himself, his clothes hanging off him in rags, marched them all the way to the magistrates. A posse of surgeons accompanied them, and the curious rag-tag of Covent Garden joined their ridiculous procession as they passed the market. When they finally got to see the chief magistrate, he let the officer go on a technicality (the arresting officer didn’t see the truncheon land). By this time, Wakley had also calmed down, and though he made a few exploratory steps to bring his attacker to justice, he didn’t press any charges or file any suits.

He would, however, have charged the College with assault, he said, if he could have. But his legal advisors pointed out that he’d have little chance of success. Instead, he used the Lancet to encourage members to abandon the Royal College of Surgeons, and to sign up with the Society of Apothecaries instead. The Society did more for their members and charged less (and he must have regretted earlier giving their board the nickname ‘Old Hags of Rhubarb Hall’).

Giving an unrealistic vision full play, he imagined a London College of Medicine, with its own Royal Charter. It would replace the Royal College of Surgeons entirely, and do everything they were supposed to do, but do it properly. It was a socialist dream. No ranks. No titles. All members could vote. Fees would be low. And all the examiners, he said, would be polite to those they examined. He even found politicians to support his half-baked idea, but it failed as soon as they tried to articulate it without Wakley lending his passion.

He’d misread the room. Surgeons didn’t want to do away with the College altogether, just reform it. And they hoped Wakley was their man.

After these violent scenes, Thomas Wakley realised there was a limit to his power as a journalist. If he wanted to make real change, he’d have to enter politics. He’d go over the College’s head, transferring his struggles from Lincoln’s Inn Fields directly to Westminster. And with that, the Wakley family home at 35 Bedford Square (nowadays the Architectural Association) into the centre of London’s social life in preparation for an election attempt.

This is straight out of a film. One that should be made.!

I was thoroughly entertained and disabused of any notions of noble institutions coming into being inevitability, with dignity and without uproarious challenge.

I love this story! My 4x Great Grandfather was almost certainly in that audience (elected to the College in 1822). I wonder what he thought about it all? Keep these wonderful stories coming!