A Renaissance loophole that allowed rich European men of science to vouch for themselves

It's wasn't as easy to be neutral as you'd think ...

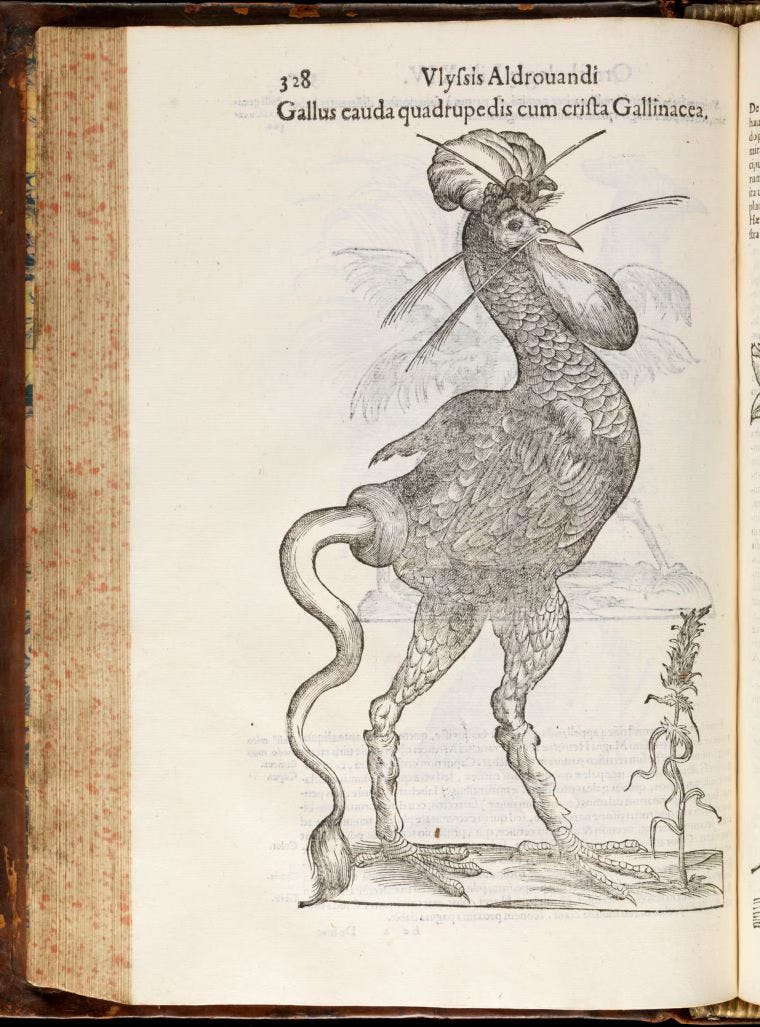

Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi once returned from an expedition to Tuscany waving a doodle he’d done of a chicken with a horse’s tail. He saw the creature in the palace of the Most Serene Grand Duke Francesco Medici, he said, and it ‘struck fear into brave men with its terrifying aspect’. Then, in 1600, he included that very image in his esteemed Ornithology (a book that also contains the memorable assertion that the human family could learn a lot from the chicken family ‘provided the rooster’s extraordinary lustfulness is not emulated’).

The eminent Aldrovandi clearly expected people to accept his fabulous claim (and many others like it). He was, after all, a respected professor at Bologna University, sponsored by Pope Gregory XIII, and a man of noble birth. Men like that, for countless generations, had relied on their social credentials to legitimise their accounts and observations.

I’ve been thinking about the chicken-horse this week, and how we’re taught that modern science did away with such unsubstantiated claims as Aldrovandi’s. And of course it did. Eventually. In the earliest days of modern science, however, it seems to have been hard for rich European men to give up their monopoly on the truth.

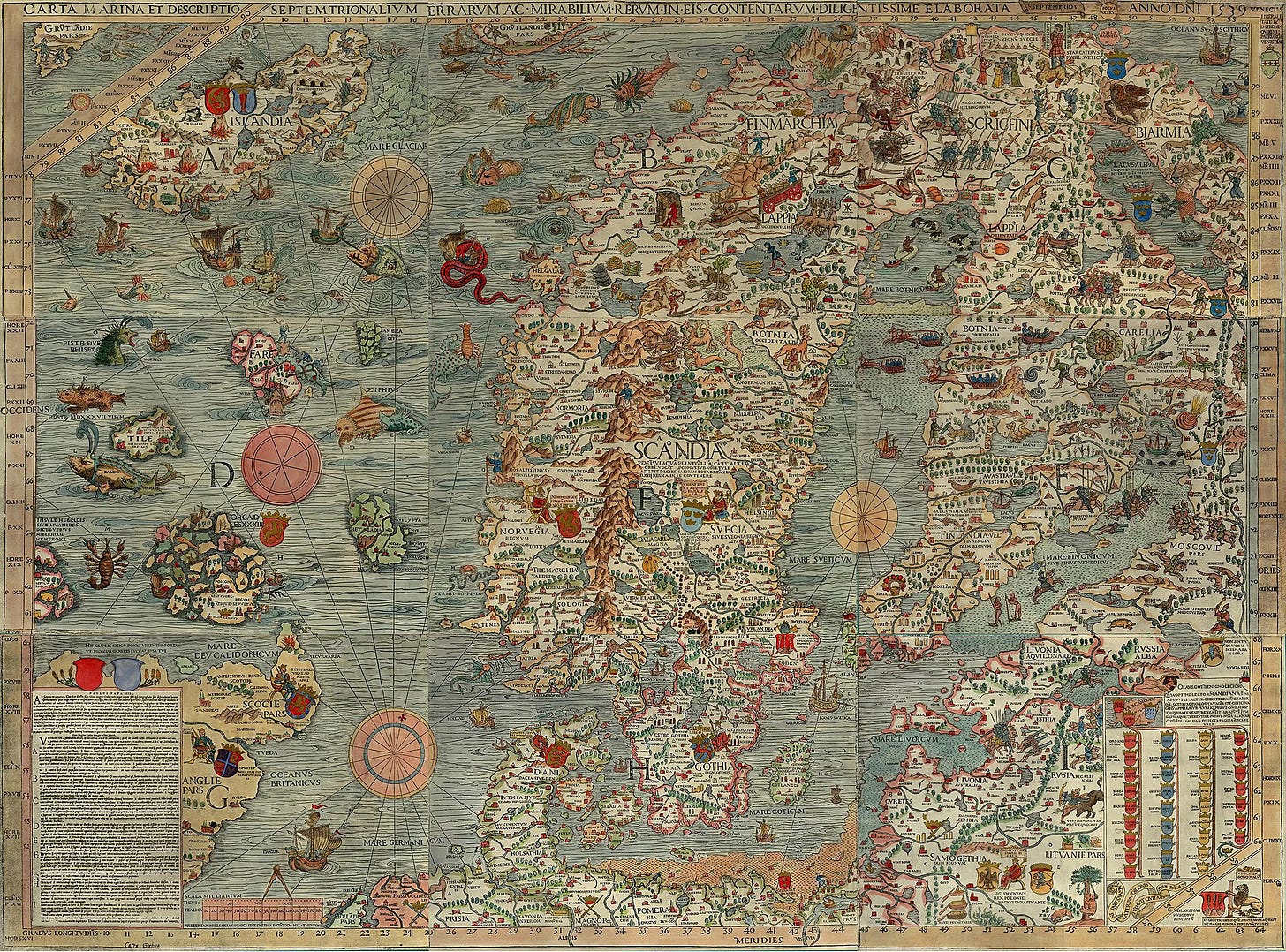

To put it crudely, modern science came about because educated Europeans felt that nothing in their books could account for what explorers of all kinds were finding beyond familiar shores. Since the Early Middle Ages, educated folk had been guided by Scripture and Ancient Greek texts – especially by Aristotle. Everything a man needed to know could supposedly be found in these texts. But those time-honoured sources were silent on matters beyond the Old World, an ignorance literally depicted in the corners of maps, where great sea serpents, dog-headed men, and other fantastic creatures stood for the unknown.

Across Europe in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, explorers and naturalists were returning from even longer voyages than Aldrovandi’s, their holds stuffed with unfamiliar plants, animals and spices. And the adventures that sailors slurred over pints of ale were scarcely creditable — even though some of them were telling the truth. An exotic world far beyond classical literature was, in this way, gradually revealing itself. As Queen Elizabeth I’s favourite courtier Sir Walter Raleigh put it, there were things out there ‘far stranger’ than what you might find ‘contained between London and Staines’.

When sacred and established texts no longer describe the world you inhabit, how do you tell truth from fabrication? The answer was simple: you must observe the natural world for yourself. Men of science like Isaac Newton saw the universe as a vast machine – a clock, with God as the clock maker. In such a vision, everything had its place in a natural order, and we could learn about it only by trusting our own experience of it. Men of science, accordingly, became confident in their own senses, seeing, listening, tasting, smelling and feeling their way to new knowledge.

The information a person derived from their senses formed a foundation from which they might establish facts, build on them, and ultimately stockpile and apply knowledge. As the philosopher John Locke expressed it 1689, the mind is like ‘white paper, void of all characters’ before being imprinted with ‘reason and knowledge derived from experience’.

The unique intellectual machinery that allows you to extrapolate knowledge from experience, experimentation, and observation is what we came to think of as modern science. It denied the existence of anything asserted without evidence, and only ever accepted anything provisionally. Men of science generally became more suspicious of information legitimated by authority. The expression ‘book of nature’ was popular in the seventeenth century – and it was far more reliable than those books of men.

The very beginning of modern science was, in this way, a triumph of empiricism and experience over authority and dogma. Man’s authority was out, and neutral, detached observation was in. But that’s not quite where the story ends. The ideal might have been more-or-less fully formed by the seventeenth century, but the reality was perhaps a little muddier. Trusting only your senses raised another problem: how do you share the fruits of your investigations if you can only trust your own experience? Men of science had a few solutions. You could demonstrate your experiment to other people, helping them see what you saw and experience what you experienced. Or you could write about what you experienced and get a ‘reliable witness’ to vouch for you1. And, you guessed it, the chief qualification for being a ‘reliable witness’ was to be a rich, European man.

So much for challenging authority.

P.S. Despite the clear dominance of the rich European, all this focus on the body and its senses made modern science a surprisingly diverse enterprise from the start — much more diverse than I think a lot of historians would give it credit for. Properly speaking, the term ‘working class’ meant little in the pre-industrial age, but those who worked with their hands – labourers, artisans, craftworkers – theoretically could thrive in modern science. In one way, they definitely did. Ordinary people already excelled in using their hands and senses, so went from having no business in the realm of knowledge creation, to being central to its economy; from being entirely absent from the production of knowledge to being highly valued for their ability to construct and operate anything from telescopes to air pumps.

Well, it didn’t quite work out like that. In reality, men of science would have a hard time trusting the observations of someone from a lower social rank (or any woman). But history is filled with nameless, faceless, ignored assistants, technicians and servants. We’ve only started to appreciate how central they’ve been to modern science. But that’s a story for another time and another column.

Tipping my hat to Steve Shapin and his his incredible 1996 book The Scientific Revolution.

As a fully paid up Privileged White European Male who lived for some time between London and Staines I’m having trouble contextualising myself in this narrative. Are you saying the world isn’t what I happen to believe, or would prefer it to be?

Also, Sir Walter Raleigh clearly didn’t live long enough to see the foxes that roam the outskirts of Hounslow at night