From the early eighteenth century, ‘nervousness’ became something of an obsession for the English middle classes. Some doctors tried to use the classification of ‘nervous disease’ to convince their patients they were special. George Cheyne – a mediocre doctor whose only claim to fame is a book on nervousness he published in 1733 called The English Malady.

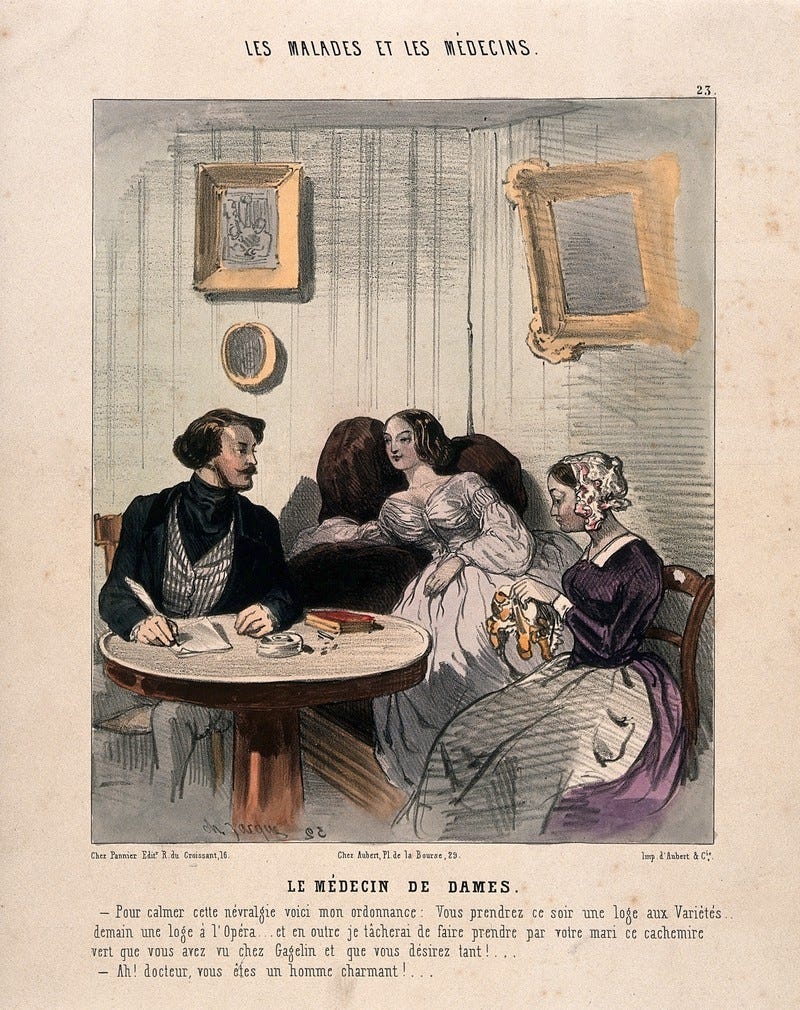

One third of all upper-class disorders could be categorised as ‘nervous’. In fact, nervous disorders only attacked people from the upper classes, he wrote, ‘the brightest and most spiritual, and whose Genius is most keen and penetrating’.

Presumably, by associating their diseases with their social status Cheyne guaranteed himself a nice flow of wealthy patients happy to be comforted that their illnesses were superior, and their superiority was moreover a natural, biological fact (and that their gout had nothing whatsoever to do with their eating pigeon, beef, venison, mutton, turkey, snipe, duck and partridge in one meal).

The upper classes loved distinguishing themselves from everyone else with their nervous diseases all through the century. You just need to look through a few Jane Austen novels to find out just how serious nervousness could be: Clarissa, the eponymous heroine of the 1748 bestseller, dies of ‘weak nerves’.

The working classes, on the other hand, were too indelicate for such diseases. Theirs were the maladies associated with overpopulation and bad hygiene. And the factory. In the decade from 1764-1774, the textile industry welcomed three revolutionary developments — the Spinning Jenny in 1764, the Water Frame in ’69, and the Spinning Mule in ’74. And these brought their own set of workplace maladies – accidents, lung complaints, ‘failure of sight’, and ‘premature old age’1.

But things would equalise at the dawn of the nineteenth century, at least according to the doctor Thomas Trotter, described in his book as the ‘late physician to His Majesty’s fleet’. Trotter wrote that nervous complaints were now becoming common amongst the lower classes. This must be because of Britain’s ‘peculiar situation’, he suggested, its climate, its free government, political institutions and vast wealth mean that a better standard of living is ‘so diffused among all ranks of people’. Now everyone had the good fortune to be nervous.

See Engels: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447946/

This dovetails well with your piece on police targeting a whole group of working class men with no empirical evidence.

To imply (or stronger) an entire group suffers from a disorder, excluding others and then attributing the condition to them, apparently on the basis that their poverty has been corrected echoes the Scottish police claims.

I suspect working class people who were diagnosed with the nervous disorders were treated differently from the rich.

Can’t help but think of the different ways those who commit crimes that are wealthy and those who are not are treated by police and in the justice system.