The Dragon in a Suitcase

Christmas shoehorned into a story about transplant surgery in the industrial revolution

A couple of weeks ago, Alistair (aged 41 ½) asked Father Christmas for a Christmas medical Story. I don’t have any, but I do have a story about transplant surgery at the very start of the Industrial Revolution. And I’ve used Substack’s AI image generator to illustrate it in a Christmassy way1.

Before we begin, let me explain that Spare Parts was, once upon a time, called Dragon in a Suitcase. That is, until my sensible editor pointed out that if I didn’t change the title, I’d spend the rest of my life answering the question ‘what does the title mean’? And there’s no short answer to that question because Dragon in a Suitcase is my name for a satirical report in the 18th December 1725 issue of Reed’s Weekly Journal.

The story begins with the business and finance men of the York Buildings Company, who at the time invested in a Newcomen steam engine on the Strand. It was part of an infant industrial age, the product of an eighteenth-century world fizzing with energy and new ideas. This particular machine was meant to provide drinking water for the capital. The 1729 ‘Foreigners Guide to London’ described it as a high, wooden tower housing a steam engine, drawing three tons of water in as little as a minute. But another publication twelve years later complained about the smoke, which was so dense it polluted the air and spoiled furniture.

The off-beat little story seems at first to have very little to do with transplant surgery. But not only does it depict the birth of the industrial and consumerist context from which modern transplants emerged, it also directly references transplantation.

Here is my slimmed-down version:

Twice a week, in a remote part of London, a group of conspirators met in a room above a stable by the Thames. The year was 1725, and they were trying to decide how to bring their latest purchase — a dragon from Libya — into the country. They hoped to terrorise the population with the family-eating, Thames-drinking, foul-breathed monster, but had to first work out how to get it through customs. After all, its tail was over a mile and a half long, which made it difficult to smuggle.

At a loss, they engaged a conjurer, who used a magical talisman to concentrate all of the dragon’s life into a small gland in its head. With the rest of the body now inert and drained of life, he anatomised it, cutting it into small parts, packing them into containers, and ordered them to be delivered to London on different ships, through different ports.

The nerves were brought up the Thames from Sweden, and the head via Norway. The rest of the body was imported through other ports and sent on to London from there. The joints, veins, and arteries came through Derbyshire, the breast by way of Worcestershire, the back and wings up through Kent, Herefordshire, and Berkshire, the belly from Cornwall, and most of the tail from the West Country. The rest of the tail — the thicker part where it joins to the body — came via Sussex, along with the teeth and snout. Peculiar though these packages were, customs officers passed them into the country unexamined, their very oddness suggesting they were part of a natural historian’s collection of curious specimens.

Once the packages had arrived safely in London, piece by piece the conjurer reassembled the dragon. With everything in place, he performed one final trick and released the life from the gland in the head, restoring vitality from nostril to tail.

With the conjurer’s task complete, a wizard from Lancashire with long, black hair and a grim countenance fed the beast on coals from Newcastle and Scotland. It began to breathe smoke so toxic that plants changed colour, confusing the city’s botanists, the walls of buildings for miles around were covered with a thick, black sheet of residue, and people breathing the pernicious fumes coughed so hard they ruptured their blood vessels.

They had a Welshman direct the dragon in its terrorism, making it exhale these paint-stripping fumes, fart noxious gasses, and drink water from the Thames — three tons at a time —disturbing all the barges whenever he said ‘Boh!’

After unleashing this suffocating monster on the world, the conspirators even convinced several families to worship it, creating a new religion which ritually transubstantiated paper into money.

The transplant reference is arcane, but is the beating heart of the story. The conjurer who anatomised the dragon focused its ‘life’ into a gland in its head, then chopped it up and had the various parts delivered to London. There, he pieced it back together and released that same spirit back into the rest of its body, unifying it once more as the creature trembled back to life.

This way of seeing life as a thing that could be locked up inside a gland seems far-fetched to say the least. Removed as we are from the forgotten physiology of the eighteenth century, it reads like a whimsical fantasy element. But it’s actually very close to what some doctors and scientists thought at the time the story was written and was the thinking behind real-life transplant surgery in the eighteenth century. The ‘life force’ was a version of vitalism, a conviction that living matter had special properties, fundamentally different to non-living matter. If you could coax life itself into a severed hand, say, it could be resurrected, claimed by the body that nourished it. At least, that was the theory.

Vitalism goes back at least to ancient Egypt, and to Hippocrates and Aristotle. Despite its ancient pedigree, it persisted and adjusted to be part of the industrial world, as much as the spectacles and pocket watches worn by the physicians who believed in it. In medicine, it went under many different names, like ‘vital spark’, ‘vital principle’, ‘animating principle’, ‘sentient principle’ and ‘living principle’.

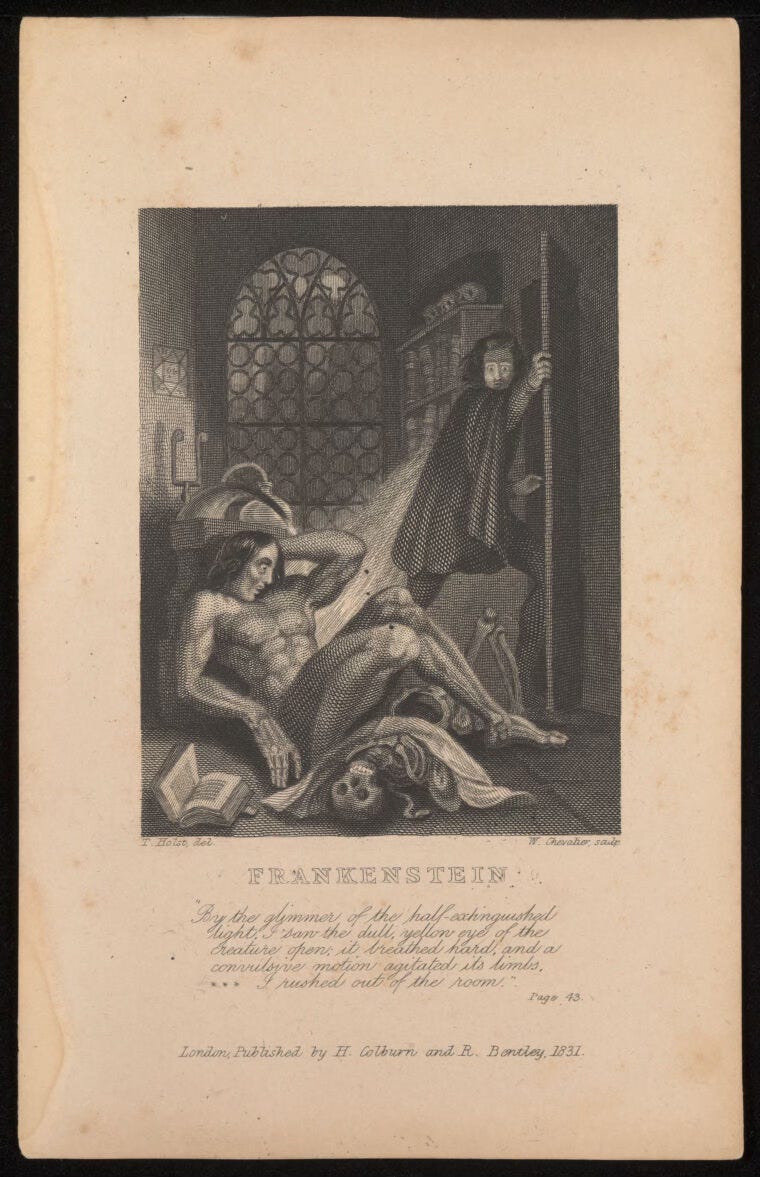

A hundred years after the Dragon story, it was still topical enough to animate Frankenstein’s monster, miscellaneous body parts grafted together, quickened by a mysterious life force.

One form of vitalism or another has been present for most of the history of transplantation, in fact for most of the history of humanity. The transfer of this mysterious principle has variously been said to extend your life, change your personality, open the door to demons, and even (as with transplant surgery and the dragon), to be the very mechanism for allowing body parts to adhere to other body parts.

We don’t talk about transplants in these terms anymore, but when you see a transplanted kidney pink up inside a human body, you see a patient’s body unconsciously claim and animate its new part. Talk about Christmas miracles. Perhaps this was a Christmas story fit for Alisair (aged 41 ½) after all.

Thank you so much for reading the first few weeks of this column. I really appreciate you, and send you my warmest, Christmassy love! If you haven’t already, please subscribe!

Judging by the results, no human artists were put out of work in the making of these images