Where did GPs come from?

Medicine had been traditionally organised in a pyramid-shaped hierarchy of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries (depicted in the seventeenth-century painting, above). By the early nineteenth century, that hierarchy had been all but eradicated.

Here’s how it was supposed to work: university-educated physicians provided diagnosis and advice. They were highly trained, would never condescend to touch a patient, and were licensed by the Royal College of Physicians.

Surgeons were more numerous, and also highly trained. They’d followed an apprenticeship, studied anatomy, walked the wards of a hospital, and were licensed by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Languishing at the bottom of the hierarchy were the apothecaries. The stench of trade secured their lowly position, and they were tasked with mixing and dispensing drugs, as directed by a physician. They didn’t need to be licensed at all, nor did they need to take any particular course of training or even apprenticeship.

That was the traditional way.

By the early nineteenth century, that hierarchy had already been collapsing for many decades because physicians were rare birds, and expensive. So, some surgeons had been billing themselves as ‘general practitioners’ and did a spot of diagnosis themselves, necessarily intruding on the physician’s territory. But this was almost acceptable. ‘There is room for one physician only,’ wrote one early nineteenth-century doctor, ‘where there may be twenty general practitioners.1’

The major collapse came in 1815 when the Apothecaries Act decreed that all apothecaries had to also be licensed – by the Society of Apothecaries.

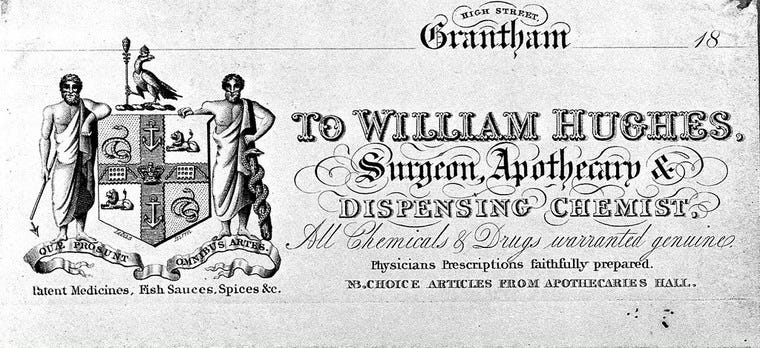

These previously unlicensed men now had to undertake an apprenticeship and five years of study. If you’re going to go to all that trouble, many thought, you might as well take surgical training as well. And so these highly trained medical practitioners started to call themselves surgeon-apothecaries. They’d perform surgery, mix medicines, and provide their own diagnoses as well. They didn’t fit into any of the traditional medical categories, but spanned them all (and sometimes more besides, especially outside London) as ‘general practitioners’.

The physicians didn’t like effectively being cut out and tried to fight back by insisting on a special claus designed to ensure their continued superiority. ‘It is the duty of every person using or exercising the art or mystery of an apothecary’, it read, ‘to prepare with exactness and to dispense such medicines as may be directed for the sick by any physician lawfully licensed.’ It was expected, in other words, that an apothecary wouldn’t try to use their new qualifications to rise above their station. But this only applied to people stupid enough to call themselves apothecaries. Everyone else called themselves ‘general practitioners’, opting out of the outdated hierarchy altogether.

What feels like a victory for the little man, however, in reality contributed to the impoverishment of huge numbers of medical men because everyone competed for the same patients.

To make matters worse, those working as apothecaries before 1st August 1815 were exempt from the new legislation (the portrait above is of one such non-qualified practitioner, William Newnham, painted in 1856). For many more years, then, a fully qualified surgeon-apothecary would still find himself competing against huge numbers of medical men who hadn’t walked the wards as they had, hadn’t paid the large fees they had, and in some cases hadn’t even bothered doing the customary apprenticeship. As far as most of the public were concerned, there was no distinction between practitioners, no discernible difference between an educated surgeon-apothecary, and just some man who fancied trying his hand at the healing arts before 1st August 1815. Both still practiced with the same title and rank of general practitioner.

Add to this the plague of quacks competing for the same patients – according to the another Regency physician, Edward Harrison, at the time they outnumbered real medical men nine to one – and the profession was aflood with medics of different stripes. Whatever their postnominals and titles, they all fished from the same pool.

Full-time GPs now earn between £68,974 and £104,086 (not including private or locum work), and some complain this is too low. Given the years of training and great responsibilities, I’m minded to agree. But GPs in the early nineteenth century had it much worse. It could take years to establish even a modest practice, and then you might be muddling along on as little as £25 per year when a skilled tradesman might make £80.

Select Committee on Medical Education (1834). Q.6299, p.171; Q.2257, p. 143. London: House of Commons.