Where did the idea of human races come from?

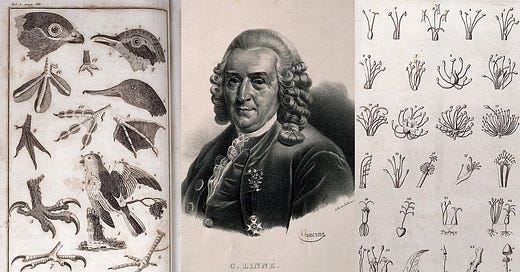

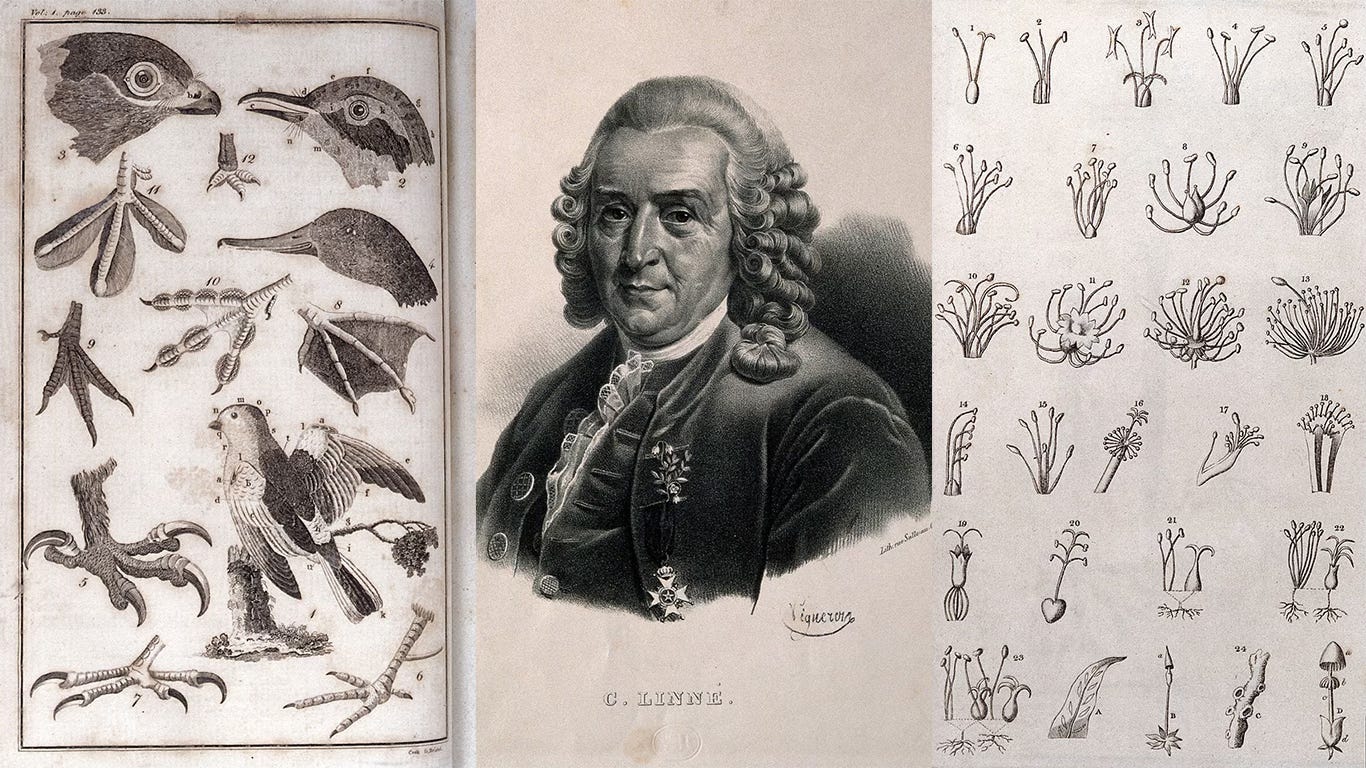

The botanist Carl Linnaeus used to refer to himself in the third person. ‘God created’, he’d say, ‘and Linnaeus organised’. In 1735 he made good on this, writing a book called Systema Naturae, in which he attempted to name, categorise, and catalogue all of nature. It was an ambitious project, but he made a good fist of it in the first edition, cataloguing thousands of species. He even subdivided humans into four varieties based on continent and skin colour.

Twenty-three years later, in 1758, Systema Naturae came into its 10th edition. Linnaeus had added some categories, redefined others and revised some of his earlier designations. Whales switched from being fish to mammals, for example, and he’d warmed up to the idea of categorising humans.

No longer was it enough to sort people according to their colour. Now each ‘race’ had characteristics. Africans were ‘phlegmatic’, relaxed, negligent and governed by impulse. Native Americans were ‘choleric’, straightforward, eager, combative, and governed by customs. Asians were ‘melancholic’, inflexible, severe, avaricious, dark-eyed, and governed by opinions. He described Europeans, meanwhile, as ‘sanguine’, muscular, swift, clever, inventive and governed by laws. If you’re familiar with classical, humoral medicine, you’ll recognise that these stereotypes map remarkably well onto to antiquity’s four temperaments and humours.

Linnaeus’s 10th edition, with its innovative taxonomy and batshit ideas about human difference, is both celebrated and disdained. It’s the foundational text of zoology. And the beginnings of race science.

See here for the Linnean Society’s take on Linnaeus and race.

At this point, I should say that I’m not an expert in race science and its evils. Anyone reading this should immediately go out and buy Angela Saini’s incredible and classic Superior: the Return of Race Science. I’ve learned a lot about race science through this amazing book.

And, though I haven’t read it yet – it came out yesterday, give me a chance! – Subhadra Das’s new book Uncivilised: ten lies that made the west1 seems like a perfect companion piece.

Anyway, let’s continue!

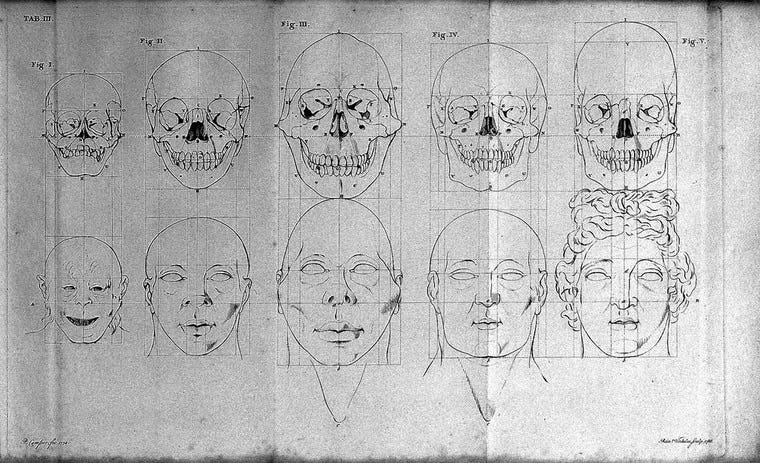

Over the decades following Linnaeus’ work, scientists fleshed out the concept of human ‘races’. The Dutch naturalist Petrus Camper in the 1770s outlined the ideal human proportions based on Classical Greek ideals. And in 1779, the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach created five human ‘races’ according to skull shape. Caucasians were the naturally superior race, but bad climate and diet had caused other races to degenerate from this white ideal, bringing us Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. If only you could put someone from one of these degenerated races into a more temperate environment and give the a proper, Western diet, thought, Blumenbach, they’d flourish and revert to their original white state.

I wrote last week about the idea of a ‘reliable witness’ and how men of science sought to separate themselves from the rest of society by embracing the idea that only wealthy, well-connected European men were capable of moving beyond the corrupt senses. Poor people made terrible scientists because they were stupid. Race science similarly gave the ‘West’ a blueprint for how European powers might position themselves as superior to the rest of the world, as the authority of modern science was projected beyond Europe. In the eighteenth century we, correspondingly, started to see the rise of colonialism and slavery. By the mid-late eighteenth century, the modern concept of race was already forming, and scientists, perhaps innocently, perhaps not, were already framing their own political views as scientific fact.

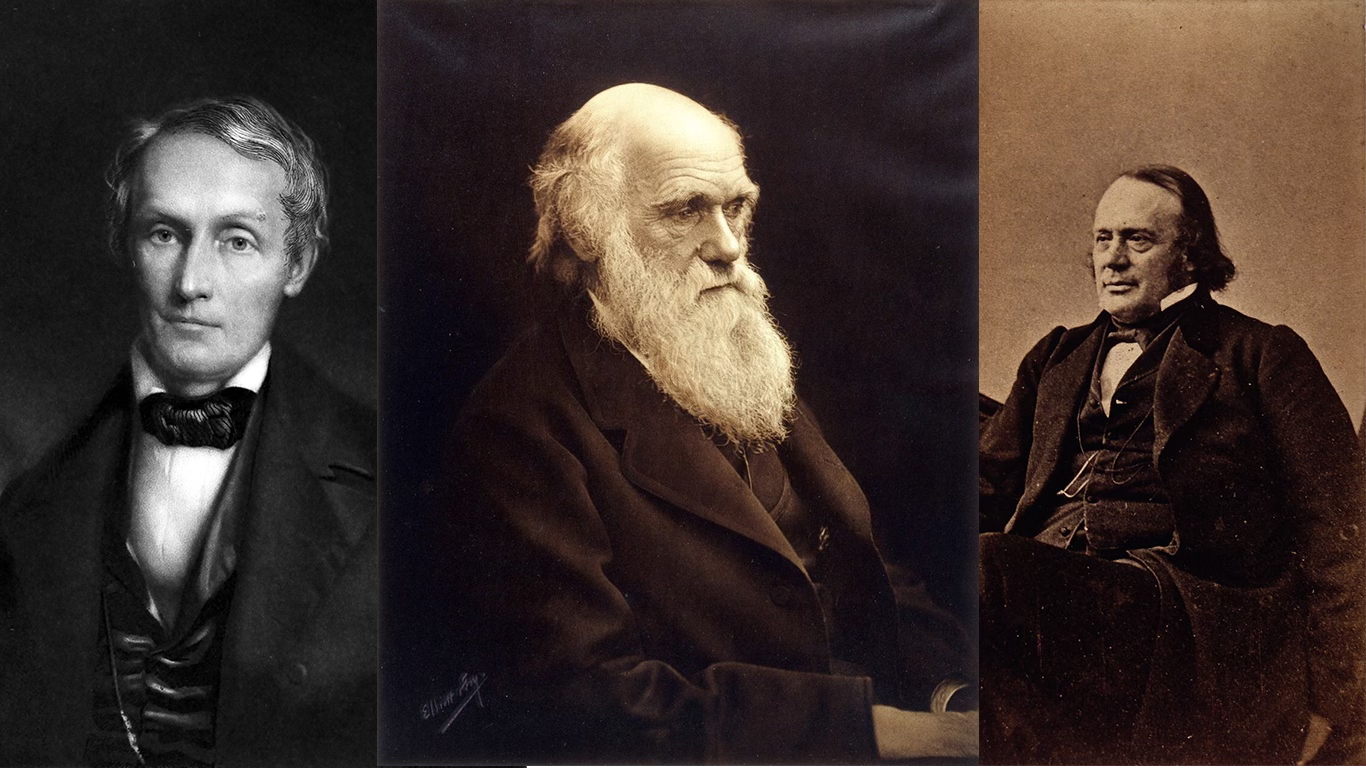

The American physician Samuel George Morton, who published Crania Americana in 1839, concluded that Native Americans couldn’t adjust to industrialised societies because their minds were differently structured. Charles Darwin popped up to support Morton and wrote about encountering ‘savages’ in Tierra del Fuego. ‘One can hardly make oneself believe that they are fellow creatures’, he said. And in the Descent of Man he predicted that ‘the civilised races of man will almost certainly exterminate and replace the savage races throughout the world’.

Louis Agassiz, Darwin’s arch critic, travelled from Switzerland to America and was the first to employ photography to document the bodies of black people, his subjects stripped naked, photographed for the purposes of ‘proving’ their inferiority to their white masters.

Related to craniology was the science of phrenology – the measurement of the skull to predict mental traits and character. And out of this preoccupation with human difference came the concept of eugenics, with the word itself coined in 1883 by Darwin’s half-cousin, Francis Galton (who also came up with the phrase ‘nature versus nurture’). Families should be given ‘marks’, Galton thought, for having certain desirable characteristics, and high-ranking families should be financially rewarded when they marry. Galton’s eugenics drew on his cousin’s famous theory of evolution to argue for the controlled breeding of populations, and in this way eliminating the weak while increasing the strong.

Galton gave a prominent lecture on eugenics in 1901, and four years later Alfred Binet invented the IQ test, inspired by Galton’s suggestion that intelligence might be inherited. Binet’s IQ test was initially a tool to help the French education system find out which children needed additional attention. But less than a decade later, psychologist Henry Goddard introduced IQ testing in the USA.

To give you an idea of the kind of man Henry Goddard was, he coined the word ‘moron’ and was a member of the Ohio Committee on the Sterilization of the Feeble Minded. Then, in the 1920s, another American psychologist Carl Brigham brought race squarely into the mix, using IQ tests to show how African-American people were ‘on the low end of the racial, ethnic, and/or cultural spectrum.’ White races, predictably, came out on top again and he issued warnings for white Americans against ‘promiscuous intermingling’ with immigrants.

Studies of human difference also influenced science in the colonies. In this area particularly, scientists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries brought cures for malaria, yellow fever, cholera and so on. These were undeniable triumphs, and in one sense encouraged trust in the efficacy of science. But the story isn’t so simple.

Imperialists capitalised on the fact that scientific discoveries like these were made by Europeans – further proof, if you were to doubt the race science, of the superiority of the white race.